THE

“KING” OF ANTS

“We

should preserve every scrap of biodiversity as priceless while we learn to use

it and come to understand what it means to humanity”

Edward

Osborne "E. O." Wilson (born June

10, 1929) is an American biologist, researcher (sociobiology, biodiversity), theorist (consilence, biophilia), naturalist (conservationist) and author. His biological specialty is myrmecology, the study of ants, on which he is considered to be the world's leading

authority.

Wilson is

known for his scientific career, his role as "the father of sociobiology", his environmental advocacy, and his secular-humanist and deist ideas

pertaining to religious and ethical matters.

Wilson was

the Joseph Pellegrino

University Research Professor in Entomology for the

Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University and a Fellow of the Committee

for Skeptical Inquiry. He is a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism. He

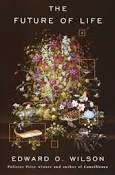

is a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction and a New York Times bestseller for The

Social Conquest of Earth and Letters

to a Young Scientist.

Wilson was

born in Birmingham,

Alabama. According to his autobiography Naturalist, he grew up mostly around Washington, D.C. and in the countryside around Mobile, Alabama. From an early age, he was interested in natural history.

His parents, Edward and Inez Wilson, divorced when he was seven. The young

naturalist grew up in several cities and towns, moving around with his father

and his stepmother. In the same year that his parents divorced, Wilson blinded

himself in one eye in a fishing accident. He suffered for hours, but he

continued fishing. He did not

complain because he was anxious to stay outdoors. He never went in for medical treatment.

Several months later, his right pupil clouded over with a cataract. He was admitted to Pensacola Hospital to have the lens removed. Wilson writes, in his

autobiography, that “[t]he surgery was a terrifying [19th] century ordeal.” Today, he suffers from the phobia of

being enclosed in a “closed space with [his] arms immobilized and [his] face

covered with an obstruction.” Wilson

was left with full sight in his left eye, with a vision of 20/10.He lost his stereoscopy, but he could see fine print and the hairs on the body of

small insects. His reduced

ability to observe mammals and birds led him to concentrate on insects.

At nine, Wilson undertook his first expeditions at the Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC. He began to collect insects and he

gained a passion for butterflies. He would capture them using nets made with

brooms, coat hangers, and cheesecloth bags. Going on these expeditions lead to

Wilson’s fascination with ants. He describes in his autobiography how one day

he pulled the bark of a rotting tree away and discovered citronella ants underneath. The worker ants he found were “short, fat,

brilliant yellow, and emitted a strong lemony odor. Wilson said the event left

a “vivid and lasting impression on [him].” He

also earned the Eagle

Scout award and served as Nature Director of his Boy Scout summer camp. At the age of 18, intent on becoming an entomologist, he began by collecting flies, but the shortage of insect pins caused by World War II

caused him to switch to ants, which could be stored in vials. With the encouragement of Marion R. Smith, a myrmecologist from the National Museum of Natural

History in Washington, Wilson began a survey of all

the ants of Alabama. This study led him to report the first colony of fire ants

in the US, near the port of Mobile.

Concerned

that he might not be able to afford to go to a university, Wilson attempted to

enlist in the United States Army. His plan was to earn U.S. government

financial support for his education, but he failed his Army medical examination

due to his impaired eyesight. Wilson was able to afford to enroll in the University of Alabama after all. There, he earned his B.S. and M.S. degrees In

Biology. He later earned his Ph.D. degree in Biology from Harvard University.

Theories and beliefs:

Epic of evolution:

"The evolutionary epic" Wilson wrote in his book On Human Nature "is probably the

best myth we will ever have." Wilson's intended usage of the word

"myth" does not denote falsehood - rather, a grand narrative that

provides people with placement in time—a meaningful placement that celebrates

extraordinary moments of shared heritage.

Wilson was not the first to use the term, but his fame prompted its usage as

the morphed phrase epic of evolution.

Wilson explained the need for the epic of evolution:

Sociobiology

Ants and social insects:

Wilson,

along with Bert Hölldobler has done a systematic study of ants and ant behavior, culminating

in their encyclopedic work, The Ants (1990). Because much

self-sacrificing behavior on the part of individual ants can be explained on

the basis of their genetic interests in the survival of the sisters, with whom

they share 75% of their genes (though the actual case is some species' queens

mate with multiple males and therefore some workers in a colony would only be

25% related), Wilson was led to argue for a sociobiological explanation for all

social behavior on the model of the behavior of the social insects. In his more

recent work, he has sought to defend his views against the criticism of younger

scientists such as Deborah Gordon,

whose results challenge the idea that ant

behavior is as rigidly predictable as Wilson's explanations make it.

Edward O.

Wilson, referring to ants, once said that “Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species", meaning that while ants and other eusocial species appear to live in communist -like societies, they only do so because they are forced

to do so from their basic biology, as they lack reproductive independence:

worker ants, being sterile, need their ant-queen to survive as a colony and a

species and individual ants cannot reproduce without a queen, thus being forced

to live in centralized societies. Humans, however, do possess reproductive

independence so they can give birth to offspring without the need of a

"queen", and in fact humans enjoy their maximum level of Darwinian

fitness only when they look after themselves and their offspring, while finding

innovative ways to use the societies they live in for their own benefit.

Consilience:

In his 1998

book Consilience:

The Unity of Knowledge, Wilson discusses methods that have been used

to unite the sciences, and might be able to unite the sciences with the humanities.

Wilson prefers and uses the term "Consilience" to describe the

synthesis of knowledge from different specialized fields of human endeavor. He

defines human nature as a collection of epigenetic

rules, the genetic patterns of mental development. He argues

that culture and rituals are products, not parts, of human nature. He says art is

not part of human nature, but our appreciation of art is. He argues that

concepts such as art appreciation, fear of snakes, or the incest taboo (Western Effect) can be studied by scientific methods of

the natural sciences. Previously, these phenomena were only part of psychological, sociological, or anthropological

studies. Wilson proposes that they can be part of

interdisciplinary research.

Criticism of human sociobiology:

Wilson

experienced significant criticism for his sociobiological views from several

different communities. The scientific response included several of Wilson's

colleagues at Harvard, such as Richard

Lewontin and Stephen

Jay Gould, who were strongly opposed to his ideas

regarding sociobiology. Marshall

Sahlin’s work The

Use and Abuse of Biology was

a direct criticism of Wilson's theories.

Politically,

Wilson's sociobiological ideas have offended some Marxists who favored the idea that human behavior was culturally

based. Sociobiology re-ignited the nature-versus-nurture debate, and Wilson's scientific perspective on human

nature led to public debate. He was accused of "racism, misogyny, and eugenics." In

one incident, his lecture was attacked by the International

Committee Against Racism, a front group of the Progressive Labor Party, where one member poured a pitcher of water on Wilson's

head and chanted "Wilson, you're all wet" at an AAAS conference in November 1978. Wilson

later spoke of the incident as a source of pride: "I believe...I was the

only scientist in modern times to be physically attacked for an idea."

“I believe

Gould was a charlatan,” Wilson told The

Atlantic. “I believe that he was ... seeking reputation and credibility as

a scientist and writer, and he did it consistently by distorting what other

scientists were saying and devising arguments based upon that distortion.”

Religious

objections included those of Paul E. Rothrock, who said: "... sociobiology

has the potential of becoming a religion of scientific materialism."

“You

are capable of more than you know. Choose a goal that seems right to you and

strive to be the best, however hard the path.aim high. Behave honorably.

Prepare to be alone at times, and to endure failure. Persist! The world needs

all you can give.”

Books:

No comments:

Post a Comment